By André Spicer, The Guardian

Whether there are more crises or we’re just more aware of them, a sense of our shared fate is key to surviving them

In 1940, as the Nazis were closing in on Paris, Walter Benjamin, the German Jewish literary critic and avid collector, knew he had to flee the city. Before leaving, he entrusted one of his most treasured possessions to his friend Georges Bataille, who hid it the archives of the French national library. This was a work titled "Angelus Novus," by the artist Paul Klee. The print is of a small angel, wings outstretched, and Benjamin describes the angel’s face as “turned toward the past,” where he sees history as “one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.”

More than 80 years after Benjamin described the unending storm of the early 20th century through the look of an angel in a painting, the Collins English Dictionary has come to a similar conclusion about recent history. Topping its “words of the year” list for 2022 is "permacrisis," defined as an “extended period of insecurity and instability.” This new word fits as we lurch from crisis to crisis and wreckage piles upon wreckage. Today, Klee’s angel would have a similar look on its face.

Permacrisis is new, but the situation it describes is not. According to the German historian Reinhart Koselleck, we have been living through an age of permanent crisis for at least 230 years – from the French Revolution to economic and foreign policy crises to cultural and intellectual crises.

During the 20th century, the list lengthened. In came existential crises, midlife crises, energy crises and environmental crises. When Koselleck wrote about the subject in the 1970s, he counted more than 200 types of crises humans faced.

Now, there may be even more. Yet, even if we don’t actually face more crises than in previous eras, we talk about them a lot more. Perhaps it is no wonder that we feel we are living in an age of permanent disruption.

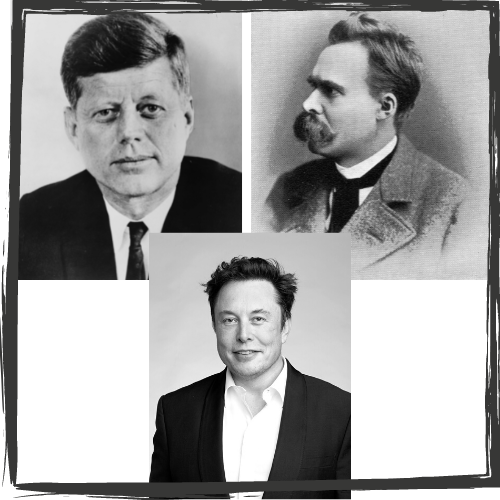

Waking up each morning to hear about the latest crisis is overwhelming for many, but bracing for others. In 1857, Friedrich Engels wrote in a letter that “the crisis will make me feel as good as a swim in the ocean.” A hundred years later, John F. Kennedy (wrongly) pointed out that in Chinese logograms, two characters compose the word “crisis” – one representing danger and the other opportunity. More recently, Elon Musk argued, “If things are not failing, you are not innovating enough.”

We know much more these days about crises' affects on us. A common folk theory states that times of great crisis lead to great creativity. However, psychological research has revealed many humans grow more rigid in their thinking and beliefs when threatened by crisis. Interestingly, psychologists also discovered “malevolent creativity,” a behavior humans sometimes demonstrate when feeling threatened by crisis. These creative ideas inflict harm, such as the development of new weapons or nefarious scams.

In a more positive vein, at least one study showed that moderate doses of crisis can build resilience. Furthermore, we become more resilient when a crisis is discussed and shared with others. In an opinion piece for Management Today, Bruce Daisley, Twitter's ex-vice president noted, “True resilience lies in a feeling of togetherness, that we’re united with those around us in a shared endeavour.”

Therefore, facing crises alone will likely lead to disaster, not just for ourselves, but for societies. The challenge our leaders face during times of overwhelming crisis is to unify us, avoiding a sink or swim mentality. Nor should they tell us things are fine, encouraging us to bury our heads in the sand. During moments of significant crisis, the best leaders create a sense of confidence and shared resilience amid the seas of change. That way, people won’t feel overwhelmed and threatened.

Plus, people will not feel alone. When we feel some certainty and common identity, we are more able to summon the creativity, ingenuity and energy needed to change things for the better.

Read the original article here.

André Spicer is a professor of organizational behavior at Bayes Business School, University of London. He is the author of Business Bullshit.