By Haley Lena, Colorado Community Media

Better understanding the complexity involved in chronic disorganization can help those affected in Colorado

Neighbors who struggle with hoarding feel ashamed and isolated. That’s partly because mainstream media has sensationalized and misportrayed this complex condition.

Even the label "hoarder" can produce shame. It's the reason the Institute for Challenging Disorganization (ICD) uses the phrase "chronic disorganization" as a more meaningful, less stigmatizing description.

Multiple studies indicate a rise in chronic disorganization in the U.S. The International OCD Foundation estimated that two to six percent of Americans live with the condition, and symptoms often appear about three times as often in elders aged 55 and older.

Dr. Trisha Hudson Matthews, chair of the Department of Human Services and Counseling at Metropolitan State University of Denver, wants to reframe the issue. She encouraged people not to internalize the sensationalized messages and view it instead as a community health challenge.

“The first thing that tends to pop up for most people is when we see hoarding, on any level, is that, ‘they’re just lazy,’” said Matthews. “Once you start applying that (label) to people ... they start to self-blame.”

What is hoarding disorder?

Chronic disorganization or hoarding is a diagnosable mental health disorder along the anxiety spectrum in which people have persistent difficulty parting with possessions due to a perceived need to save them. According to the American Psychiatric Association, attempts to discard the items create distress because the owners have attached emotional value to the objects as a way to cope with inner turmoil or trauma.

The National Institutes of Health website points to a systematic study of the condition involving psychology, psychiatry and related fields ongoing for nearly two decades with scientific mention as early as 1947. A genetic component may be involved.

Distilling the condition, Matthews said, “It’s the inability to give up anything because everything carries significant meaning."

Chronic disorganization can cause problems in relationships, leading to family strain and conflicts, isolation and loneliness, unwillingness to have anyone else enter the home and an inability to perform daily tasks, such as cooking and bathing in the home.

Matthews added that the disorder can result in severe mental and physical health effects, deteriorating finances and, when left untreated, can lead to legal issues if a municipality condemns a residence.

Hoarding is different from collecting. Collectors search for and acquire specific items to organize them intentionally for display. Chronic disorganization is a private behavior cloaked in shame and distress undermining quality of life.

Why does hoarding happen?

About 75 percent of people living with chronic disorganization have co-occurring mental health conditions, like generalized anxiety, major depression or obsessive compulsive challenges, states the International OCD Foundation on their website.

Matthews also indicated that trauma is a key marker. It can be carried forward from childhood or, commonly, after losing someone significant at any age.

“It really depends on how we cope with the external things that happen in life,” said Matthews. “Typically, when ... hoarding, for whatever reason, (people) cannot release it and they won’t come for help because of the shame and embarrassment.”

The impact of sensationalized media

Television reality shows about chronic disorganization and movies inaccurately portraying it perpetuate two false narratives: people who live with hoarding challenges are disgusting and simply by cleaning the residence, the person is cured. In fact, the situation is far more complex and layered.

Matt and Krista Gregg, owners of Bio-One of Colorado, a specialized cleaning service in south metro Denver, agree that the condition isn't accurately portrayed. “When you see it on TV, it’s the most extreme scenarios,” said Krista. “That’s the only real exposure people have had and there’s a lot of shame that’s portrayed. There’s a lot of sadness that’s portrayed.”

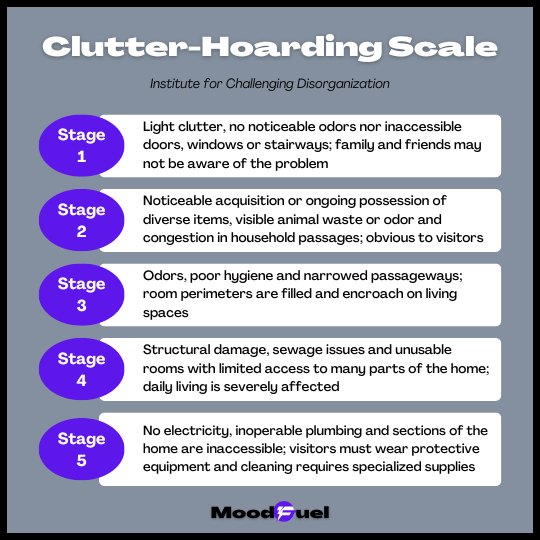

To diminish shame, the Greggs walk community members through the five stages of the Clutter-Hoarding Scale as developed by ICD:

Strategies for support

Everyone leads a busy life and it’s easy for any home to become cluttered. However, if all the stuff effects the residents physically and mentally, it's time to ask for help.

Many local companies offer strategies to help residents declutter and clean without judgment. ICD also lists 258 certified consultants around Colorado specializing in the different categories of chronic disorganization.

Trending cleaning methods enable residents to view their possessions from new perspectives. The KonMari Fundamentals of Tidying advocates parting with items that don’t bring joy while thanking them before discarding or donating them. Margareta Magnusson in her book The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning encourages readers to downsize by getting rid of unnecessary possessions to improve their lives and avoid burdening their loved ones.

Most importantly, emotional healing through decluttering the mind is an integral part of the recovery process. Matthews said it's important to talk with a mental health professional about the meaning of items and the sense of loss and grief associated with letting them go. Therapy will help people distinguish between chronic disorganization and being a bit messy.

This article was republished with the permission of Colorado Community Media, which connects, educates and empowers readers along the Front Range as the state's largest source of hyper-local news, information and advertising. Read the original article here.