By Renata Hill, Moodfuel

Despite a deadline and consent decree, Colorado illegally detains defendants judged incompetent, preventing them from receiving treatment or facing trial

Coloradans living with serious mental illness who have been criminally charged but can't participate in their own defense learn one thing well – patience – and they learn it in jail. Colorado excels at detaining defendants judged incompetent before trial. Months pass as these neighbors wait in cells without familiar social supports nor treatment as the backlogged competency process grinds on.

State can't adhere to its own deadline

Indefinite detainment is unconstitutional, but for more than a decade, Colorado has been unable to provide adequate and timely evaluation and treatment within the 28 days mandated. The seriousness of the crime is irrelevant. About one-third of defendants with serious mental illness (SMI) or developmental or cognitive challenges have been charged with only misdemeanor offenses, like public urination. Yet, many of them have been waiting longer for treatment to restore them to competency than the length of a sentence had they faced trial and been judged guilty.

A Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) document refers to this fact: "people charged with misdemeanors in the competence process are more likely to be found incompetent, take longer to treat and are more likely to be found unrestorable." In other words, people with SMI and less serious charges end up with the most intensive, most expensive treatment services for the longest periods of time. This aspect doesn't include the wait time for treatment.

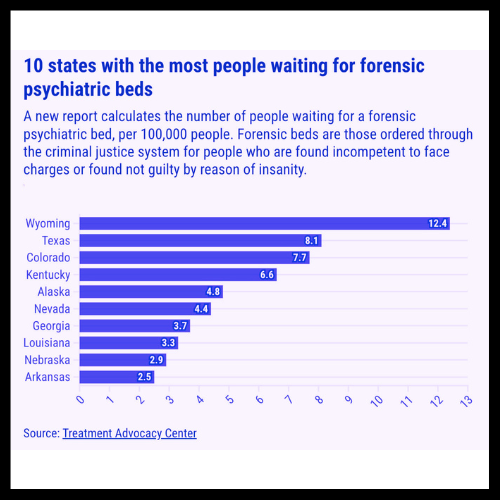

Earlier this year, the Treatment Advocacy Center, a national research and policy organization supporting the seriously mentally ill, ranked Colorado third in the nation for the number of its residents waiting for competency treatment.

According to an article by The Colorado Sun, the backlog is mainly due to staff and facilities shortages. The Office of Civil and Forensic Mental Health (OCFMH) shut down sections of the Colorado Mental Health Hospitals in Pueblo and Fort Logan during the pandemic where competency defendants would usually reside until treatment. Pueblo is still operating below capacity.

The goal of hiring additional, trained mental health personnel has become a thorny problem itself. Most Colorado healthcare companies and agencies are struggling to fill vacancies for all roles despite competitive salaries and five-figure signing bonuses. A quick survey on ZipRecruiter of various locations around Colorado yielded more than 1,230 vacancies for registered nurses alone.

Human resources experts believe the pandemic continues to impact healthcare workers. Workers on the front lines concur.

"People I know are still burned out (from dealing with the pandemic). The public just doesn't understand how hard it was on us," said a certified nurse assistant working in Pueblo who wanted to remain anonymous.

State pays millions of dollars in fines each year

Waiting in jail for competency treatment is not only inhumane, but expensive. In 2019, a federal consent decree ordered the state to start paying fines, capped at $12 million per year, until treatment services occur within the 28-day deadline. As of Feb. 2024, the State has paid $41.3 million in fines to an umbrella fund that subsidizes local competency deflection programs.

Currently, OCFMH reports that 374 people are waiting for competency treatment for an average of 94 days, but some residents spend more than six months in jail. One person languished for 418 days.

"My son has been in the Eagle County jail for eight months," said Laurie Slaughter, a resident of Eagle County who visited Denver during a mental health advocacy day at the Colorado State Capitol. "I haven't been able to see him at all." She participated in Mental Health Colorado's "Care Not Cuffs" event on Mar. 6.

Slaughter spoke directly to Rep. Kyle Brown and Rep. Judy Amabile about legislation to untangle her son and his mental health challenges from the state's legal system. Amabile's own son lives with serious mental illness and the two women wiped away tears as Slaughter expressed her worry and frustration.

Deflection programs are one effective solution

National competency experts, such as Judge Steve Leifman of Miami-Dade County, know this complicated problem can't be solved only by staffing and new facilities. During a Care Not Cuffs presentation in Denver, he described himself as “the gatekeeper to the largest psychiatric facility in Florida — the Miami-Dade County Jail." Twenty thousand people in need of mental health treatment arrested for misdemeanors and low-level felonies funnel through the jail annually.

Leifman learned through two decades of tough experience and much research that deflection programs are key to unlocking the competency treatment backlog. People living with SMI or developmental challenges who are judiciary-involved should enter community wraparound programs not jail, he stated. The "wraparound" aspect includes housing, counseling, medication management and vocational training.

He said, "If people could avoid going to jail before trial at all, treatment wait times would decrease substantially."

Legislation could offer relief, if passed

Legislators have proposed more than 30 mental health-related bills during this year's General Assembly. One bill addresses exactly the solution Leifman advocated.

At the beginning of March, Amabile and Rep. Javier Mabrey introduced HB 1355 to reduce the glaringly long treatment wait times. This bill would create a deflective, wraparound-service program managed by Bridges of Colorado.

Eligible defendants would receive an individualized care plan and services over 182 days with a possible 91-day extension. If they complete the program satisfactorily, the court would dismiss their charges. No jail time before or after treatment.

Although similar bills in past years have not fared well in the statehouse, Amabile believes this one has traction. In an email, she said the more holistic approach of HB 1355 gives it a good chance of passing.

Governor Jared Polis, new Commissioner Dannette Smith of the Colorado Behavioral Health Administration and other government stakeholders hope that a combination of increased staff, more facilities and effective deflection programs will expedite the competency process. Those 374 unlawfully detained people and their families will have to wait and see.

Watch Rep. Judy Amabile speak about HB24-1355 (Measures to Reduce the Competency Waitlist) during a press conference on Mar. 26, 2024.

Video excerpt of Rep.Judy Amabile's press conference explaining her reasons for sponsoring HB24-1355. Video courtesy of Mental Health Colorado.

The full video is available here.