By Allison Marshall, Moodfuel Contributor

A millennial woman sees the parallels between her own mental health journey and that of Jake Lloyd, the actor known for his role as young Anakin Skywalker in the "Star Wars" franchise

In May 1999, my "Star Wars"-obsessed family crammed into a showing of "Episode 1: The Phantom Menace." It was then, as an eight-year-old, I found my favorite movie for the rest of my childhood. Even now, almost 26 years later, the film holds a special place in my heart. I put hundreds of hours on our VHS copy, and when we upgraded to the DVD, packed with bonus material, I scoured every digital menu and watched it all.

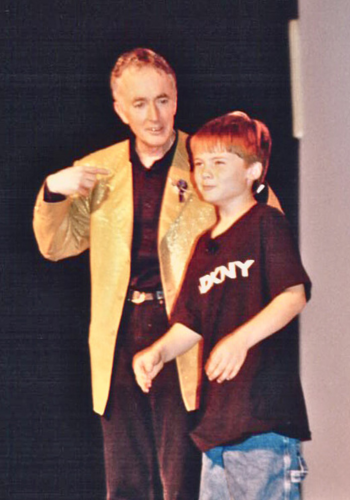

In the bonus material, I learned about the extensive search for a young actor to play Anakin Skywalker. After auditioning at least 300 children, George Lucas and his team selected eight year-old Jake Lloyd, sweet-faced with dusty blond hair and blue eyes.

As an eight-year-old myself, I thought it was incredible that one kid could rise above the rest and find what I saw as glamorous stardom, a life full of cameras and attention. I followed news of him even after the critics sneered at "Phantom Menace" and Lloyd silently disappeared from Hollywood.

After Hollywood lights: Jake Lloyd’s life with a brain disease

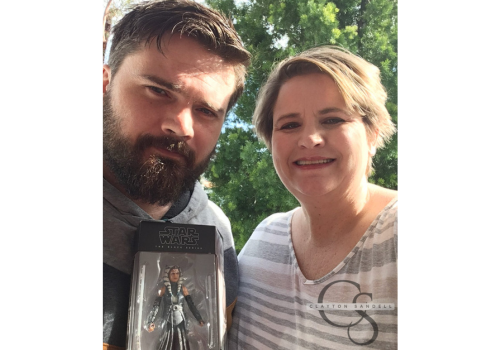

Lloyd was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 2008. His mother, Lisa Lloyd, detailed his years-long struggle in a 2024 interview with Clayton Sandell for Scripps News. Suffering from anosognosia, a neurological condition in which a patient doesn't accept or recognize their illness, Lloyd often resisted treatment.

In 2015, he led police on a multi-county, high-speed chase before crashing his car. He spent 10 months in jail while Lisa Lloyd fought to get him treatment. At the time of her 2024 interview, her son was living in a mental health facility in Southern California after suffering a severe episode of psychosis.

Lloyd spent 18 months receiving inpatient treatment. After emerging, Sandell followed up with Lloyd and the story was picked up by People Magazine and other entertainment media.

In the Sandell interview, Lloyd said he was ready to “honestly live” with his diagnosis, comply with treatment protocols and felt “pretty good.” Now, he lives in a rehabilitation center to continue his treatment with the freedom to come and go. He watches TV and plays video games.

His life today may seem simple compared to his Hollywood existence, but for the thousands of people who struggle with serious mental illness, the focus on Lloyd's progress is a welcome sign of hope.

Hopeful stories are scarce, but important.

Alone: my own battles with psychosis

During several low points in my own mental health journey, I've needed a hopeful story.

My struggles began when I turned 20. The first warning sign was severe depression. In 2015, after a 72-hour stint of insomnia, I experienced my first delusion: I was bone-deep-certain I’d had an epiphany about human existence, one foreshadowed all my life and that everyone on the planet eventually experienced.

Two days later, after a trip to the emergency department where a physician gave me Klonopin, I was able to sleep and my head cleared. I searched for my epiphany online and found nothing matching my experience. Once I realized my belief was contrary to physical evidence, I knew the epiphany had been a delusion. I swallowed my nagging concern and told absolutely no one.

In 2016, the epiphany happened again. Then, it happened over and over, every weekend, while I was receiving outpatient care for my depression. Tossing and turning at midnight, alone in my apartment, a clap of thunder sounded outside and I thought destiny was calling me to walk into the storm.

I experienced a barrage of thoughts: My apartment staircase led to Heaven; I'd hung up the phone on someone inadvertently destroying the universe; and the government was ruthlessly controlled by people with red hair. The mismatched images and delusions lasted five days. When the brain fog cleared, I was in a psychiatric hospital. I’d suffered my first episode of severe psychosis.

In the weeks following, continuing my outpatient program for depression, I would listen to the other patients talk about managing their depressive symptoms and feel like an alien in the room. Depression seemed like a manageable monster, but now the doctors were using words like "bipolar," "psychosis" and "schizoaffective." These words filled me with deep-seated terror.

The first medications I was prescribed didn't banish the referential delusions. I was convinced I could hear subliminal messaging on the radio telling me I was an insect that needed to be eradicated. The second set of medications made me so tired I couldn't function.

Simple existence seemed impossible. How could I live independently or graduate college, let alone achieve anything I dreamed for myself?

All the stories I knew about people who struggled with psychosis were bleak and often ended in tragedy. For a time, I was certain normalcy was over and my illness would inevitably claim my life.

In January 2017, I experienced my second severe psychotic episode and had to stay in a poorly operated psychiatric hospital until I was lucid again. I missed two weeks of classes, and my boyfriend broke up with me.

Still, in December of the same year, I walked the stage in a cap and gown to receive my bachelor’s degree. Then, an internship turned into a full-time job.

High off my accomplishments and believing myself totally better, I quit taking my anti-psychotic medication and avoided my doctor. Four months later, in April 2018, I suffered a third severe episode.

Wrapped in delusions, I drove my car until I ran out of gas on the access road to a highway. Other drivers called the police. An ambulance picked me up and I entered the same poorly operated psychiatric hospital.

I lost my job. My doctor switched me to an anti-psychotic injection which she administered herself. I lived with my parents for a few months – not what I wanted to do at the age of 27.

I got another full-time job and moved in with roommates. Somewhere in the cycle of progress, disaster, backslide and baby steps, I found a way to access hope even though I still felt alone in my journey.

Then, with treatment and support, I stabilized. I learned to recognize my warning signs and weathered my fourth psychotic episode in February 2021, safely at home. With loved ones helping me take my emergency anti-psychotics, I felt secure and was able to find my way back to lucidity more quickly.

Entering 2025, I will celebrate four years completely psychosis symptom-free.

Why it matters: sharing our stories smashes stigma

According to an article in The Denver Post, about 260,000 adults and children living in Colorado need treatment for severe brain illnesses, like major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. The article also stated that funding is disproportionately weighted toward managing people whose disease has reached catastrophic levels instead of toward prevention.

As a result, people with unmet mental health care needs experience what advocates call "churn" – going to emergency departments for help, interacting with law enforcement, being incarcerated, losing what stability they had and often ending up unhoused.

While I was fortunate and didn't experience all those aspects, I do wish my old self could see me now. I also wish people on the depression and psychosis Reddit forums could see that a happy, hopeful existence is indeed possible.

Before and during the early years of my diagnosis, I bought into a myth accepted by professionals and the public: schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are progressive illnesses inevitably ending in violence or death.

While tragedy is certainly part of many stories, focusing on it obscures a beautiful truth: With treatment, the story can have a very different ending.

Dr. Richard Warner, the late founder of Colorado Recovery in Boulder, stated in his book, The Environment of Schizophrenia, “Over the course of months or years, about 20 to 25 percent of people with schizophrenia recover completely from the illness. All their psychotic symptoms disappear and they return to their previous level of functioning.”

A 2021 study repeating his methods showed an even stronger percentage of complete recovery at 37 percent.

Even for people who don't recover fully, many lead meaningful lives with varying degrees of independence and ability. Some speak about their journeys and tell hopeful stories, too.

Lloyd is currently living at a rehabilitation center and looking forward to Star Wars day on May 4, 2025 with his mother. Whatever the future may hold for those of us with serious mental health challenges like me, it's hope enough for today.

I’m so glad Lloyd feels well enough to start telling his story. It’s in sharing our stories that we change the narrative.