By Haley Elaine Strom, Moodfuel

Restorative justice programs can create healing and accountability, two essential ingredients for survivor mental health

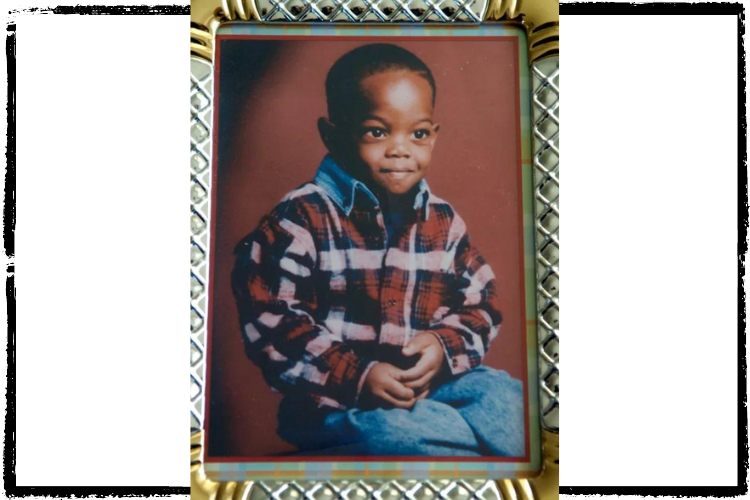

In the winter of 1995, three-year-old Casson Xavier Evans was shot and killed by teenagers in a gang-related incident in Denver. After her toddler died in her arms, Sharletta Evans said she heard the voice of God asking her if she could forgive the killer, the “one who caused me the most harm.” She said yes.

Evans found her outlet for forgiveness through restorative justice.

Restorative justice is an alternative criminal justice process that involves reconciliation between crime survivors – as some restorative justice organizations refer to people impacted by crimes – and offenders. The aim is to decrease recidivism among offenders and to give crime survivors an avenue of healing.

Ten years ago, restorative justice was reserved for first-time offenses, often involving theft. In Colorado, where recidivism rates have been as high as 60%, there seemed to be a need for more restorative justice opportunities.

The Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit founded by Just Mercy author, Brian Stevenson, attributes high recidivism rates across the country to the lack of restorative processes in prisons and jails. Their team describes incarceration as “overcrowded, violent, and inhumane jails and prisons that do not provide treatment, education, or rehabilitation.”

The killers of Casson were sentenced to this un-rehabilitative domain for life. When Paul Littlejohn, a member of the gang that killed Evans' son, was escorted out of his sentencing, he smirked at her. Branded in her memory, this smirk ultimately inspired Evans to put in a request for a face-to-face restorative justice mediation two decades later. Her request took 3 years to receive approval because never before had restorative justice been utilized for such high-risk crimes.

Evans worked with state representative Pete Lee, a criminal defense lawyer who previously volunteered with a restorative justice organization, to testify for the first bill on restorative justice becoming law. In 2012 Senator John Hickenlooper signed the bill. Now, restorative justice can be initiated by crime survivors to address violent crimes involving death.

Seventeen years after her son was killed, Evans became the first person in Colorado to engage in a high-risk dialogue through the state’s pilot program. She engaged in 6 months of pre-conferencing, where she met with restorative justice mediators to prepare for her meeting with Littlejohn.

Then, she participated in the face-to-face meeting that she had pictured for so many year. Littlejohn apologized for his expression in the courtroom that day two decades earlier and, more importantly, took accountability for the killing of her son, though he was not the actual shooter.

Next, Evans met with Raymond Johnson, the youth who had fired the shot that had killed Casson. When she saw Johnson, she realized she felt much differently than many crime survivors do who confront the person who caused them grievous harm.

“When I laid eyes on him, I felt nothing but compassion,” she said. “I didn’t have the hostility and resentment and hate and revenge. My spirituality overrode those thoughts.”

Having converted to Islam in prison, Johnson shared her spiritual devotion and commitment to redemption. While the restorative justice pilot program did not directly impact Johnson’s sentence status, Lee said it made him a better candidate for rehabilitation.

From that point on, Evans advocated for Johnson’s release, which required testifying for new legislation on life without parole for juveniles tried as adults. God again gave her strength. Johnson asked Evans to be mother he never had growing up and she accepted.

On Dec. 21, 2021, Johnson left prison. As Evans stated to CBS News on that day as she sat in an Aurora park with her son, Calvin Hurd, her "adopted son" Johnson and a photo of Casson, "I'm here today with my three sons. I feel accomplished. I feel like all the work was not in vain. I also feel very emotional that Casson is not here."

Although faith influenced her redemptive journey, Evans said restorative justice offers non-religious individuals the same opportunity for forgiveness. “When you step into restorative justice, you’re stepping into a spiritual component that people don’t even know about because what’s happening is you’re stepping into a place of grace – a place of second chance, a place of redemption,” Evans said. “That is why it will impact regardless of what people think of their stances with God.”

A 2006 study supports her perspective. Of 20 homicide, attempted murder, sexual assault and theft crime survivors, most were able to abandon hatred because they felt sincere remorse from the offender after a restorative justice mediation. Also, recent research in positive psychology finds that forgiveness is beneficial for mental health and is linked to reduced anxiety and depression.

The language of restorative justice also benefits crime survivors’ mental health. For example, using the word “survivor” helps facilitate a sense of control. One study found that victimizing crime survivors exacerbates insecurity, lack of control, injustice and lack of self-esteem. The term “survivors” returns the power to the hands of crime survivors.

The process of creating an agreement with the offender also contributes to the crime survivors' mental health. A 2013 study done in Belgium and Canada, where some American restorative justice practices originate, found that of 26 crime survivors, all achieved a greater sense of control after hearing their offender state in their agreement that they would not commit the crime again.

Even with the praise restorative justice programs receive, critics have said the positive impacts are limited. One study on the confines of restorative justice said that crime survivors are sometimes pressured into mediations, and mediators are not adequately trained to provide emotional support. Most studies supporting these critics are outdated because of new legislation and evolving practices. Current restorative justice practices emphasize that the survivor must be at the center of the mediation and that pre-conferencing must take place until crime survivors are ready to confront offenders.

The key to creating restorative communities is recognizing that it takes time for crime survivors to heal and feel ready to meet their offender. For Evans, it took 14 years. Over time, though, restorative justice exemplifies how accountability and healing can coexist. The main difference from conventional criminal justice processes – besides plummeting recidivism rates – is that a mediation, versus a trial alone, recognizes and prioritizes the mental health of crime survivors.

Haley Strom is a student at Colorado College studying Psychology and Journalism. She works as an EMT and is a Fellow with the Mentora Foundation, an impact-driven nonprofit based in New York City. After college she hopes to continue her education in the field of mental health.