By Ann Schimke, originally published in Chalkbeat Colorado

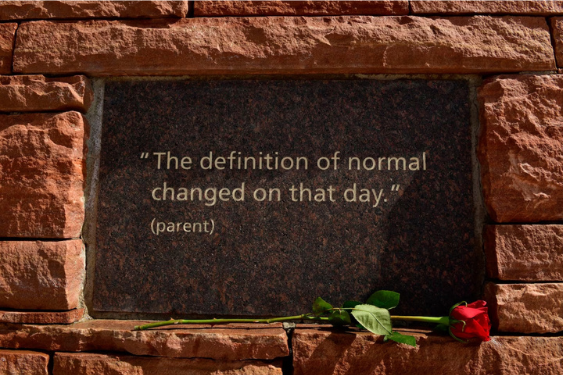

Heather Martin was a senior at Columbine High School in Littleton on April 20, 1999 when 12 classmates and one teacher died in the mass shooting that traumatized the nation. Even as she tried to move on with her life, she carried the trauma of that day inside her — often in ways that surprised her.

The following year, during a community college class, she cried during a routine fire drill, confused and embarrassed by her reaction. “I hadn’t remembered, until that very moment, that the fire alarm had been going off while I was barricaded for three hours before the SWAT team came,” she said.

She struggled with panic attacks, an eating disorder and insensitive comments from instructors. Eventually, Martin dropped out of college.

Today, Martin is a high school English teacher in Aurora who prioritizes making her students feel safe and giving them tools to understand and cope with trauma. She’s also the executive director of The Rebels Project, a nonprofit that supports survivors of mass tragedy. Here, she talks about her journey toward mental health.

The moment she decided to become a teacher

After the shooting at Columbine in 1999, I struggled a lot with trauma while attending community college and ended up dropping out. One day, while filming some B roll for a documentary called "Grieving in a Fishbowl," I was asked to flip through my high school yearbook. I found where my English teacher had signed: “I hope you major in English and become a teacher - your students would love you!” it read.

It seems I had forgotten for a while where I wanted to go, but I eventually found my way back. After 10 years and a long road of healing, I went back to school, finished my degree and earned my teaching license.

Trauma manifested during her initial college experience

I had extreme anxiety and unpredictable panic attacks — or at the time I thought they were unpredictable. I developed an eating disorder, started ditching and failing classes and even tried recreational drugs. I attributed many of these things to “normal” college behavior and refused to acknowledge that it had anything to do with the shooting. I told myself, “It’s been (blank) months, I should be fine.”

I had an English teacher assign a final essay that had a prompt related to school safety or guns in schools. When I finally worked up the courage to tell her why I couldn’t do the essay, she said it was required and if I didn’t do it, I would fail the class. I never went back to that class and, ultimately, ended up failing. I was already questioning my “right” to be traumatized, and her dismissal was extremely harmful.

When I took English again, I was assigned to write a 2-3 page personal narrative about an event that impacted me. This was about a year after the shooting, so I decided to actually tackle writing about it. I wrote upwards of 10 pages. On the due date, I printed my essay and brought it to the instructor. I told her how long it was, but I did not tell her the content. I wanted reassurance that the length was okay.

She said she would probably just grade me on the first few pages. Again, I felt dismissed and that my experience didn’t matter, and again, this amplified my questions about whether I had any right to feel and be traumatized. Again, I failed English class because I stopped attending.

My students love to hear that I failed English class twice in college!

Personal experience influences her teaching approach

I was a student who often felt like I wasn’t seen or noticed in school. I did just enough to stay off everyone’s radar — never a super-high or a super-low performer. As a teacher now, I look for students who may feel like I felt and am sure to connect with them. Also, obviously, the shooting and my subsequent healing journey help to drive my mission to make my classroom (and school community) as safe as I can — both in the physical sense and the emotional sense.

Her passion: The Rebels Project

I co-founded the organization in 2012 with three other classmates from Columbine in the aftermath of the Aurora theater shooting. It’s named for the Columbine High School mascot. We wanted to provide support that we didn’t have access to after the shooting at our school — a space to share, connect and heal alongside others who understand what it’s like to experience a similar event. Everybody on our leadership team has experienced a mass trauma themselves which drives our decisions in every project.

We connect survivors from all across the world. We hold support meetings, travel to impacted communities, educate the public on ways to support trauma survivors and host an annual survivor retreat. We do this all as volunteers.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy.

Read the original article here.