By Tanmoy Goswami, Sanity

Beware of the reckless boom in mental health apps

"Our research has found that, in gathering data, the developers of mental health-based AI algorithms simply test if they work. They generally don’t address the ethical, privacy and political concerns about how they might be used."

Piers Gooding and Timothy Kariotis aren't activists or luddites. Gooding is a senior research fellow at Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne. His work focuses on the law and politics of disability and mental health. Kariotis is a lecturer in digital government and PhD candidate in digital health at the same university. He researches the design of digital mental health technologies.

Together, they are experts on a subject that ought to keep you up at night: the dangerous rise of unethical, privacy-destroying, venture capital-fattened mental health apps.

Few things terrify me as much as the dystopia that is mental health technology. Mozilla Foundation, which published a report on the privacy features of mental health and prayer apps earlier this year, called the majority of them "exceptionally creepy" because "they track, share, and capitalize on users' most intimate personal thoughts and feelings, like moods, mental state, and biometric data."

"Despite these apps dealing with incredibly sensitive issues — like depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, domestic violence, eating disorders, and PTSD — they routinely share data, allow weak passwords, target vulnerable users with personalized ads, and feature vague and poorly written privacy policies," the foundation added.

The idea of informed consent from users does not exist in these badlands, where tech solutionism runs riot, and your every thought and emotion is a data point to be sliced, diced and monetized. The lack of regulation in several markets makes it a free-for-all.

In Stanford Social Innovation Review, Greta Byrum and Ruha Benjamin explain the risks of this trend:

being watched private information surveillance

Welcome to the world of surveillance capitalism, where all human experience is reduced to data and often weaponised against the very human from whom the data is extracted. In techbro land, this tainted data is the ultimate aphrodisiac to lure in smitten investors.

$$$ galore

On the face of it, mental health apps have a strong use case. They are cheap or free to use. They can prevent stigma by giving users the choice of seeking help without physically exposing themselves to other humans. They can address the vast gaps in traditional mental health care.

In practice, however, all these noble motives – which call for patient, long-term, structural work – don't stand a chance against the Silicon Valley cult of "Move Fast and Break Things."

Perhaps the most nauseating example of this was when suicide hotline Crisis Text Line was found sharing 'anonymised' data on callers with its for-profit spinoff company. The incident led to a temporary furor, but it failed to create a sustained industrywide reckoning.

I have a clear and simple stand on privacy: any app that claims to help people who might be anxious or desperate for help or both, must explain their privacy policy in simple language first thing in the user onboarding flow. Most apps continue to couch this critical information in gobbledygook and bury it in the product's innards.

Gooding and Kariotis of University of Melbourne, who recently wrote about mental health apps in Scientific American, are the latest addition to a growing chorus warning us about the imminent mental health app-ocalypse. They also draw attention to another glaring problem – even academic research on these apps is being conducted with blinkers on.

When Gooding and Kariotis surveyed 132 studies that tested automation technologies, such as chatbots, in online mental health initiatives, they found:

- 85 percent of the studies didn’t address how the technologies could be used in negative ways despite some of them raising serious risks of harm

- 53 studies used public social media data – in many cases without consent – for predictive purposes like trying to determine a person’s mental health diagnosis and none grappled with the potential discrimination people might experience if these data became public

- Only 3% of the studies appeared to involve substantive input from people who have used mental health services thereby excluding the participation of those who will bear the consequences of these technologies.

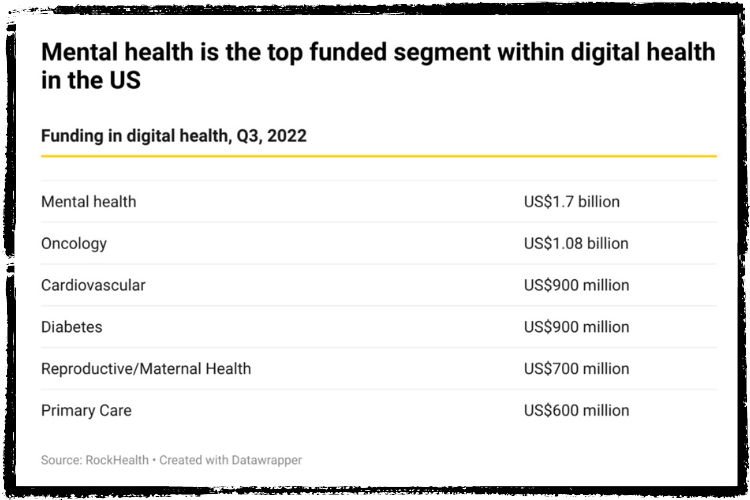

In the absence of any systematic scrutiny, there's little to stop the mental health tech sector from becoming the next Atlantis. Venture capital investments in mental health startups hit a record $5.5 billion in 2021 up from $2.3 billion in 2020. While digital health funding has cooled in 2022 in the wake of a worldwide economic crisis, mental health is still the highest funded clinical indication, beating oncology and cardiovascular innovations. The frenzy won't abate any time soon.

According to one market research firm, the market for artificial intelligence-driven solutions in mental health is slated to balloon from $880 million in 2022 to nearly $4 billion in 2027. The paper concludes that this trend "bodes well for the market."

Except what's good for the market is often not good for people.

At this point, it is important to reiterate that not everyone questioning technology is an anti-tech activist. Can technology play a role in making mental health care more accessible? Who wouldn't like to believe that? But is technology in its current form the answer to the deep systemic and structural crises in mental health? Beware of the Kool-Aid.

"The first step in countering the gospel of tech solutionism is simply to question the presumption that new or revised technologies are the solution to any given social problem," wrote Byrum and Benjamin. "We need to also consider that the technology that might be working just fine for some of us (now) could harm or exclude others – and that, even when the stakes seem trivial, a visionary ethos requires looking down the road to where things might be headed. Those who have been excluded, harmed, exposed and oppressed by technology understand better than anyone how things could go wrong. Correcting the path we’re on means listening to those voices."

First published in Sanity, an independent, reader-funded mental health storytelling platform.